Introduction to Part I

Dapple grey is a favorite color among many folks for good reason — it’s both beautiful and striking. And, truly, there are few things quite as lovely or ethereal as a nice dapple grey! Yet for our sculptures, it can be an extraordinarily challenging color to paint with all its characteristics, variations, and nuances that can give even the most experienced painter fits. Indeed, there’s a big reason why dapple grey takes significantly more time and skill to paint! So in the spirit of making this process a bit easier and more clear, let’s talk about grey dappling from a practical standpoint and hopefully we can kick our results up a notch.

In this Part I then we’ll begin our exploration with some basic ideas about dapple grey and some reasons why it’s so tricky to paint. Once we grasp these preliminary concepts, we’re in a much better position to really dig into Part II with more clarity and confidence. So let’s just dive in…

The Problem With Pattern Recognition

The human brain can be thought of as a sophisticated pattern recognition machine, adept at finding and interpreting patterns of all kinds. Really, when you think about it, nearly everything can be broken down into a pattern in some way so it makes sense that evolution shaped the brain thusly. In fact, the brain loves patterns so much, it’ll simply make them up where none exist which is where we get our gambling addictions, logic fallacies, conspiracy theories, and superstitions.

Now one would think that pattern recognition is a boon when it comes to painting something like dapple grey, and we’d be right — but only to a point. Because the problem is our brain is actually too good at pattern recognition, fixating on it too quickly and powerfully which ends up becoming a real liability when it comes to capturing authentic horse color. Why? Because it’s exactly in our pattern recognition response where we get the dreaded regimentation in our dappling paintwork. What’s regimentation? It’s when our dappling becomes too uniform in its characteristics over the sculpture, driving it away from realism and towards contrivance and stylization. And the problem begins quickly as our brain will regiment our dappling nearly instantly the moment we touch brush to sculpture and right under our noses to boot. It’s simply what it does. It’s why our hands will fall into a dappling habit so quickly if we aren’t careful to mediate this strong tendency. And it’s also why our Eye — our knowledge base, tastes, biases, aesthetic, and style — will skew towards uniformity in our dappling as our brain prejudices us against the organic randomness of nature.

As a result, the moment we begin to dapple our piece is the moment we must be vigilant against regimentation and we do this in four ways. First, we pay close attention to our references and really lean into them as we dapple. Taking our cues from authentic nature is nearly always the better policy. Second, we reset our Eye by taking refreshing breaks. This not only allows us to rest a bit, as all that focus can be exhausting, but it also breaks up the routine of dappling to hopefully inject more variation into the overall mix. Third, we use specialized tools like dappling brushes to do more of the work for us in a way that better randomizes the results (discussed in Part II). And fourth, we employ artistic tricks and strategies to help steer us away from uniformity and habit and more towards organic authenticity (discussed in Part II).

The point being, we have to work against our own brain in order to render a more realistic dapple grey and those who are most adept at this tend to create the most convincing dapples. As such, our prime directive then is to avoid regimentation as much as possible to better express organic realism and that’s within our grasp with just a bit of know-how.

Things to Remember about Dapple Grey

Dapple grey is mostly a function of heat in that the areas that are hottest tend to lighten faster. This is why those characteristic areas grey out as those are areas of thinner skin or they have blood carrying networks closer to the surface (like veins or capillaries). It's also why blanketing, neck sweating, or even the mane itself can cause a pale patch. In fact, that's all a dapple really is in most cases: A lightened warm capillary "burst" of branches. And because capillaries are so individualistic in shape, being random in their branching, so a grey dapple is, too. Really, if you look closely, they're like snowflakes, no two exactly alike. They may share a similar look, yes, but each is as individual as a fingerprint.

Dapple grey is a progressive color that develops as the horse ages. As such, foals are born dark and so dapple grey develops from dark to medium to light as the horse grows older. The extreme version can result in a white horse. In short, foals typically aren’t born dapple grey. In fact, a foal destined to grey out will sometimes have white hairs around the eyes (“goggles”), muzzle, dock, inside the ears, or even ticked throughout the coat.

It’s a composite color made up of the coat color and white hairs. Being so, dapple grey can occur on any coat color and in conjunction with any pattern or markings.

There are many types of grey that describe the effect the gene has on the coat color. For instance, there are rosegreys (dapple grey on bay, chestnut, dun, etc.), steelgreys (a grey coat without dapples), fleabitten grey (tiny flecks of the coat color that remain during the graying out process which can also develop in conjunction with dapples), porcelain grey (dapple grey on black) and a whole host of variations in between. However, it’s important to know that dapple grey isn’t roan though it often gets confused with that color.

“White,” the lightest stage of dapple grey, isn’t Cremello (also erroneously termed “albino”). Dapple greys have dark skin (except under white markings) whereas Cremellos have pink skin.

Not all aged horses grey out pure white either, but sometimes retain some pigment, especially on the points, in particular the joints, and sometimes in the mane and tail. On the other hand, some youngsters may grey out rather quickly. Sometimes the rapidity of the greying progression is hereditary and sometimes individual, or both. So while dapple grey’s progression is linked to the horse’s age, it’s not necessarily an accurate indicator of age. Fleabites aren’t an accurate indicator of age either because they can pop up rather early in the greying process.

Although dapple grey has telltale characteristics, within those “rules” the color is quite diverse and varied; no two dapple greys are alike. The individual qualities are as unique as giraffe spots or zebra stripes.

Some Tips

Think of dapple grey as a pattern, not a color. If regarded as a pattern with the dapples and the dark networks entombing them, painting it becomes more clear. So look for dapple patterns and network patterns as though you were deciphering an appaloosa, pinto, or zebra pattern. And use the skills you’ve learned translating appy and pinto patterns. For example, on appaloosas, we often learn to see dark spots on a light area whereas with pintos, we learn to see white laid onto a coat color. However, with dapple grey, we have to apply both skills at the same time. In other words, don’t just see white dots on dark areas and dark patterns under white dots — see both and how they relate to each other and morph over the regions of the body.

Think of the various shades of dapple grey as different levels of intensity of the dark portions. In other words, a dark dapple grey has a high intensity of dark areas and a light dapple grey has a low intensity of dark areas. A medium dapple grey is the most diverse, having a wide range of intensities on the same horse.

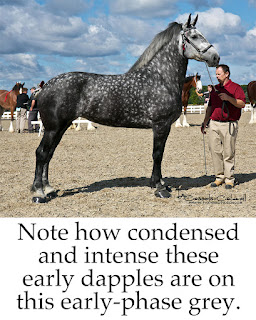

The dapple grey pattern often begins at the crown, facial features, throat and jugular, elbow area, flank, inner legs, groin, and in the groove between the semitendinosus muscle and biceps femoris muscle on the hindquarter. Though there are exceptions, the first dapples tend to emanate from the coat small and condensed to then enlarge and diffuse as the pattern progresses. On a classic dapple grey, dapples are often white or shades of pale grey. On a rosegrey, dapples can be any variety of tones often ranging from rust to mocha to gold to rosy to grey to white, depending on the body color.

Sometimes dapples can be muddled in some areas and distinct in others so look how they change in how striking or muted they are over the regions of the body. Likewise, sometimes the dark areas can be very pronounced in some areas and very diffused or lightened in others so don't forget to pay attention to the nature of the dark networks as well.

There are six components to dapples: Size, shape, placement, hue, intensity, and detail. Employing all six qualities will help us avoid an artificial-looking “rocking horse” impression and a more “grown,” natural look in our final effect. Really, the better these six qualities, the more convincing our dapple grey will be…

Size: Dapples can vary in size compared to their neighbors and on different regions of the body. For instance, sometimes the dappling on the neck, shoulder, or hindquarter can be a bit larger than the dappling on the barrel. However, sometimes they can be sized a bit more uniform as a whole as it all depends on individual variation of the pattern. Point is, pay attention to dapple size in a reference as it relates to its kin, across the body, and to the overall effect.Shape: Every dapple is unique in shape, like a snowflake, so be mindful of this as we paint. Like some dapples are rounder or oblong blobs, some are crystalline-like, some are like puzzle pieces, some are like bursts or stars, some are like branches, and some are like checkers, and lots more in between. So pay attention to all the different shapes seen within a dappling pattern.Placement: Dapples often vary in their spacing from each other, with some being tightly packed (with narrow dark honeycombs) while others more loosely packed (with broader dark honeycombs) so avoid an even spacing between all the dapples.Hue: Dapples can vary in color on different areas of the body, something especially relevant for rosegreys. So look for hue, tone, tint, saturation, and value in each dapple as it relates to its neighbors in order to pinpoint the right color for that specific dapple.Intensity: Dapples can vary in brightness during different phases of the pattern or over different areas of the body so pay attention to which ones are brighter or more subdued.Detail: Dapples can be rich in little details like branching, mottling, “ghost trails,” diffusion, and graininess so look for the little things that add so much interest.

Dapples tend to have a crystalline-like structure and fit together reminiscent of jigsaw pieces. This is because of the structure of the heat-sink capillary networks that tend to be the generators of the dapples themselves. As such, they tend to be most intensely pale in their middles to diffuse outwardly into the surrounding dark network. Dapples can have a pattern with the hair growth, too, especially in the flank and loin area. Also notice that dapples are often quite different in type on different regions of the body. In other words, we really can’t apply the same type of dapple to the shoulder as we did to the barrel as we did to the pectorals, for example, so pay attention to references.

The forearms, gaskins, and sometimes the lower haunch can have “sunbursts” and “lightning streaks,” or white hairs forming streaks radiating outward in a burst or branch-like fashion, criss-crossing the areas. “Ghost trails” are also thin trails of light hairs that can connect dapples together so look for those as well in references, especially on the shoulder and neck. “Shadow trails” are swaths of dark color that arc over the body, remnants of the dark portions that are shrinking. Also look for “wash outs” of white, or areas of white diffusion into the dappled areas that will soften or break up the dark networks encasing the dapples. Additionally, the lower leg tendons can be lighter while the coronets can be rimmed in light hairs as “bracelets.” Streaking and patchiness can also occur throughout the lower leg, especially in medium dapple greys. However, dark point color tends to stick to the joint areas most often even as the horse greys out.

Markings and patterns become more diffuse into the grey coat as the pattern develops, most notably on the legs and face, with the exception of muzzle markings which tend to remain more or less crisp.

The color of the mane, tail, and feathers are subject to a lot of variation so pay attention to them in references and life study. In this, rosegreys tend to have the most arresting variations, some even having flaxen or bold rust-colored manes and tails!

Study lots of photos and do field study up close to learn the nuances of the pattern. Indeed, a hefty mental library for dapple grey helps us draw from its commonalities as well as infuse eccentricities and details that add novelty and authenticity to our paint job. Indeed, it’s important that each of our dapple grey paintjobs be distinctive since the pattern in life is as unique as a fingerprint.

Conclusion to Part I

Clearly mimicking a convincing dapple grey isn’t as straightforwards as it would first seem, is it? There’s loads more to it than first meets the eye! But therein lies so many treasures for us, gifts that can take us on a wonderful journey of discovery, progress, and fascination. In this way, learning to better paint a dapple grey can unlock so many other skills and fire up our gumption and inspiration in novel new ways. And once we come out the other side having succeeded, we’ll have gained a newfound confidence and clarity in our abilities, the true gift this pattern has to offer us.

So in Part II let’s continue the discussion with more ideas on rendering this complicated pattern with more believability to get one step closer to our lofty painting goals. Until Part II then, delight in dappling to explore the wonderful world of color, effect, and pattern to discover our true artistic potential!

“Great art picks up where nature ends.”

— Marc Chagall

I’d like to thank both Lesli Kathman of The Equine Tapestry and Lynn Cassels-Caldwell of Snowdrift Studio for the use of their photos in this blog series. Thank you gobs, gals! You helped the really dapple up this blog series in the best way! Thank you!