"Conformation" is a ubiquitous concept in the horse industry and so it is with equine collectibles, influencing everything from buying decisions to placings to aesthetics. Yet it has many variables, each a sphere of fascinating study. In overview, it helps to determine function and usability according to the horse's discipline. Each discipline then often commands its own points of conformation, sometimes specifically so. Conformation also factors into our personal taste, those things that tickle our fancies...or not. What's more, each breed, sub-type, region, and family line can have its own particular conformation, making it distinctive and consistent. Adding to this, the different genders can have their own secondary sex characteristics that can differentiate one from another. Conformation can also differ between individual horses, entailing those quirks that make each one unique. Going further, the different ages can introduce their own effects as the body matures. Horsemanship, conditioning and management all have their effect, too, by changing the nature of the muscle condition and even some alignments. All in all then, the issue of conformation is a complex one full of nuance and detail. For these reasons, the better we grasp the concepts, the more informed choices we can make.

But a few points beg mentioning. First, it's important to understand that conformation isn't the same as anatomy. They are two different subjects. For example, an Arabian and a Clydesdale both have the same anatomically structured cannon bone, but it's conformation that makes them different. Or a Saddlebred may have a different slope to the hip than a Quarter Horse conformationally, but the pelvic girdle is the same anatomically. Or a Lusitano can have a more convex skull and a Thoroughbred a straight skull conformationally, but both those skulls are anatomically consistent. Essentially then, anatomy is the blueprint of the species and conformation entails the superficial variations of that blueprint, often generated by selective breeding. In this sense, anatomy relates to what's realistic whereas conformation largely deals with what's preferred. So an error in anatomy is to make an error in realism whereas an error in conformation is to create an error in perfection. As such, a sculpture can be conformationally perfect but anatomically flawed, rendering it unrealistic. On the flip side, a sculpture can be anatomically close to correct (no sculpture is 100% accurate as only nature can do that) and be conformationally flawed, but still be realistic. What does this mean? Well, it's not a bad idea to remain open to the possibility that perhaps the artist chose to infuse some conformational issues or physical quirks into their piece for their own creative reasons. How that affects our own sensibilities is our own prerogative, but it's something to consider.

Second, everyone has their own opinion of what's conformationally "perfect" and that's okay! But it does put an artist in a precarious position since it seems there will always be someone out there disapproving of their piece. Complicating the issue is that breed type can be folded into conformation, and how "right" that is can be highly subjective to taste, even fads or fashion. More still, some breeds have or are morphing into new forms to adapt to changing times, creating a bit of friction over what's considered authentic. This means that the idea of perfection is more a bubble than an X-marks-the-spot, and that's okay too because a bubble allows for more variation to appeal to different tastes. It also helps to hedge the bet towards genetic diversity, an overriding concern for any breed with closed books.

Third, it can be useful to categorize conformation into a hierarchical order for evaluation. For this, we can break it down into three specific categories, in order of importance:

- Functional conformation: Structures consistent to the equine blueprint that ensure well–being and soundness according to the target discipline. In a sense then, it's "biologically practical."

- Type conformation: The bubble of characteristics that differentiate breeds or types, often referred to as "points of type." It also incorporates gender, regional, or familial differences.

- Aesthetic conformation: The structures that define our own tastes. It may also relate to individual variations, trends, fads, or fancies, making it the most subjective factor.

Functional conformation is the foundation of "using" structure. It bears mentioning, however, that exceptions always exist as there are plenty of hardworking, sound horses with what could be considered flaws by some. Moreover, usability can also depend on the nature of horsemanship, management, and conditioning so those should be considered as well. Above all though, it's good to remember that the horse is biologically based first on function and perhaps it's best our evaluations are as well. As for type conformation, it definitely plays an important role in what's desirable, creating the recognizable "outline" of a breed. Think of it as "brand identity." At its most basic, it's what separates an Arabian from a Quarter Horse from a Clydesdale from an Exmoor. More refined, it's what differentiates the *Morafic family from the *Bask family of Arabians, for instance. We should understand however that type conformation is best when balanced with functional conformation, avoiding exaggerations that compromise function. Lastly, aesthetic conformation entails all those little touches that add "flavor" to appeal to different tastes. For example, some people like dainty heads on their Quarter Horses whereas others prefer the more robust type of head.

But all in all, let's discuss a little bit of functional conformation since it tends to be more objective. In this, let's explore some of the most common conformation hiccups in realistic equine sculpture so we can learn from them.

Back Too Short

When we discover how to measure proportion effectively using bony landmarks, it becomes evident pretty quickly that the equine back is normally longer than we may believe. This is perhaps because many of the collectibles we grew up with were stylistically very short-backed, some unnaturally so, conditioning us to favor it. Yet nature needs the equine back to be a normal length for biomechanics and to accommodate the organs, and in particular for mares, to gestate foals. Now this isn't to say a long back is the ideal alternative as it can be significantly weaker for riding. It's to say that the equine back should fit within an average spectrum of what's normal. That said, however, we know that certain breeds have backs on the shorter end of the spectrum. The Arabian, and some of its derivatives, can indeed have one less vertebra on occasion, for example. Yet this is perfectly fine if not overly exaggerated like it can be in art. But more still, every individual, type, and breed has its own distinct spectrum, so it's important to pay close attention to the back length when designing a sculpture. Stallions and mares can differ as well on occasion, helping to make mares appear "lower to the ground." Even different ages can have their own distinctions since the spinal column is among the last to solidify its growth plates. Foals are a good example of a really distinct type of back length compared to the rest of the body, for instance.

Here's a basic guide for proportions where everything is easily based off the head length. However, please understand this is just a guide and not applicable across the board. (Also understand that the horse depicted is believed to be a mare.) Each breed, type, family line, gender, age, and individual has their own specific set of proportions. This guide is just a baseline to gauge those variations. It's a springboard, not dogma.

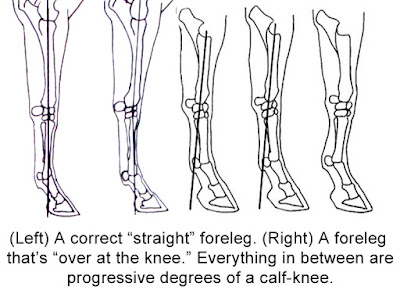

Calf Knees

This is a particularly common error perhaps because there's some confusion as to what constitutes a "straight leg." Even conformation books can get it wrong in illustrations.

Functionally, a correct, straight foreleg has a radius meeting the carpus at more of a 90˚ angle thereabouts. Therefore, a plumb line will bisect the radius and bony column to emerge at the bottom of the bisected cannon bone and behind the coffin bone, onto the frog.

However, this alignment can appear over-at-the-knee to the uninitiated, and many conformation books depict calf knees as correct as a result. Yet a calf knee is a significant fault as it weakens the forelimb and can even be prone to bone chips in the carpus or tendon injuries in the lower leg. Now it's not to be confused with a foreleg under stress such as we sometimes see with the planted forelimbs of racehorses in that support phase of the gallop. A proper foreleg will usually withstand these pressures whereas a calf-knee generally won't, resulting in injury.

On the other hand, genuine over-at-the-knee structure is usually an injury to the foreleg’s tendinous check system causing the carpus to project forwards without adequate support.

Literal Straight Forelegs

Another aspect of evaluating straight forelegs is from the front. Here the correct anatomical alignment is a slightly knock-kneed stance just like our own femur with our tibia. In other words, the equine cannon and radius shouldn't be aligned straight up and down like a rod, but angled inwards a little bit at the knee, towards the median. It's a subtle alignment, but perfectly natural. In fact, if a straight line between the cannon and radius does exist, the horse can be bow-legged in front.

Literal Straight Hindlegs

Similarly, the idea of a “straight” hindlimb has been interpreted to mean literal straightness when viewed from behind, an error quite common in conformation books. It's no surprise then why we'd find this hiccup in sculpture. By "literal straightness" we find that the plane of the hindlimb is straight forwards from stifle to toe, meaning that the toe points forwards when standing square. Yet this is actually a form of bowleggedness.

In their natural configuration from behind, the hindlimbs are oriented on a slight outward plane from stifle to toe, with all the bones aligned on the same plane when standing square. That means hind hooves typically point a bit outwards at the toe because, biomechanically, the stifles must clear the broad posterior portion of the belly. This isn’t to be confused with cow-hocks in which the hindcannons angle away from each other. Correctly planed hindlimbs have parallel hindcannons. Now it should be mentioned that as the hindlimb is extended backwards more, it tends to straighten out as the stifle is drawn away from the belly, even rotating a bit inward in extreme extension sometimes. But life is full of exceptions, of course, so pay attention to reference photos.

Here's Ellie demonstrating that outward plane of the hind leg.

Crooked Hindlegs

A good rule of thumb for hindlimb alignment is measured from the side in a plumbline from the point of hip, to the point of hock, and down the back of the cannon. This plumb line is often consistent whether the hind limb is planted forwards or backwards when standing. Keep in mind, however, that balance shifts can influence these articulations away from the plumbline.

Post-legs occur when the hindleg is placed in front of the plumbline whereas camped-out occurs when the hindleg is placed behind it. Sickle-hocks occur with too much angulation at the hock, orienting the hindcannon away from the plumbline. Post-legs don’t have much reach and are prone to involuntarily locking the stifle which can injure the stifle joint. On the other hand, camped-out legs can be more unstable and wobbly, often prone to spavins.

However, because they move primarily in non-suspended gaits, it's claimed that some gaited breeds can be regarded a little bit differently. Specifically, some believe that acceptable angulation lies within a range from the ideal plumbline to one that touches the front of the hindcannon. Nevertheless the hindlegs shouldn’t be more angled than this or be sickle-hocked. (On a side note, post-legs in gaited horses are a significant fault because this can lead to ESAD over time.)

Now inspecting from behind, the hind cannons should be parallel to each other. If they divert away they're cow-hocks and if they converge at the hoof, they're bow-legged. What's more, some draft breeds should be "close-hocked" which shouldn't be confused with cow-hocks. Instead, "close hocks" are when the cannons are properly parallel to each other, but are situated very close to each other, sometimes even touching. The Clydesdale is a good example. It's believed this places the feet neater into crop furrows.

ESAD and DSLD

We also have to consider two crippling conditions: ESAD and DSLD. ESAD (Equine Suspensory Apparatus Dysfunction) is a term for a problem in the suspensory apparatus, which inhibits the horse from properly supporting himself through the lower leg. It appears to be caused by several things ranging from injury, overstress, peculiar conformation to genetics. It can be associated with coon-footedness, and so often presents as very sloping pasterns with a broken axis at the coronet when standing square. Similarly, DSLD (Degenerative Suspensory Ligament Desmitis) is a painful, bilateral degenerative condition of the suspensory ligaments, usually in the hindlegs, which hinders their supportive properties. As DSLD progresses, the fetlocks sink increasingly downwards, causing the pasterns to become progressively parallel to the ground while straightening the stifle and hock. Think of a post-legged horse with sloping hindpasterns when standing square. The causes of DSLD are also suspected to be genetically based, but can be brought on by overstress or peculiar conformation as well. Unfortunately, however, some sculptures exhibit ESAD and DSLD perhaps because the artists didn't know what these conditions were.

Shoulders and Hips Too Short

When it comes to motion, a long shoulder and hip are ideal with many breeds. In this, the shoulder from the tip of the wither to the point of the shoulder should be about one head length while the point of the hip to the point of the buttock should also be about one head length. The long shoulder provides scope to the forelegs while the long hip helps to provide that necessary rear drive powerhouse. However, these can vary sometimes so pay attention to references.

It should be mentioned that the slopes of the shoulder and hip are also important but differ according to breed and discipline as it influences motion quite a bit. For this reason, it's important to pay attention to them in references.

Puffy Joints

Another common problem with sculpture, puffy leg joints that resemble "balloons" can indicate injury or pathology. In life, the knee, hock, and fetlocks should be crisp and "clean," displaying the distinct, characteristic bony landmarks and bony shapes consistent to their anatomy. At times some of the ligamentous and tendinous features can be seen as well. The same could be said for the cannons and pasterns though they tend have this issue to a lesser degree.

Balance Inconsistent to Breed Type or Discipline

The "uphill" or "downhill" balance of the body is a function of performance and therefore often of breed type. For example, those breeds classically bred for riding such as the Arabian, Morgan, Iberian, and Saddlebred have level or even slightly "uphill balance." Think of a sedan. Many breeds meant for jumping and eventing can be of a slightly more uphill balance. In contrast, those breeds destined for bursts of speed tend to have "downhill" balance such as many Quarter Horses and some Thoroughbreds. Think of a drag racer.

What is uphill or downhill balance? Well, it's the relation of the base of the neck (where the neck connects to the torso) to the LS-joint (the hinge joint between the last lumbar and the sacrum that curls the pelvic girdle under the body) when standing. If the base of the neck is more or less level with the LS-joint, the horse is level-balanced. If the neck base veers higher, then the horse is "uphill." And, predictably, if the neck base veers downwards, the horse has downhill balance.

Yet some sculptures don't factor this in which can be a problem. For example, a downhill Saddlebred or an uphill foundation QH can both be considered off-type.

Too Skinny or Too Thick a Tailbone

The size of the tailbone is an extension of the spine, so at the root it implies the size of the spine itself and should, therefore, be in anatomical scale to the sculpture. However, many sculptures have tailbones that are too skinny indicating a weak spine. In contrast, others have tailbones that are far too big and out of scale.

Pathological Hooves

Finding a good foot can be difficult in sculpture because what constitutes a quality foot may not be understood. Indeed, many references or conformation books actually depict problem hooves so it's important to have an independent knowledge base. Even so, its exact qualities are still being discovered and debated in science and it'll be fascinating to see where it all pans out. The subject is quite complex though as science is revealing just how nuanced horse feet truly are. Curiously, it seems there's no "one size fits all" kind of good foot but a spectrum since the foot molds itself to the horse's lifestyle. I wrote an extensive series on the foot already in Steppin' Out: Hooves From An Artistic Perspective (a 12-part series) so please refer there for a comprehensive look. (Now admittedly, I need to update it according to some recent studies, but all in all, it gives a pretty good basic idea of many of the issues involved.) In particular, this segment, this one, this one, and this one give an overview of the possibilities within the bubble of "good foot."

Specifically though, many sculpted hooves have problematic relative proportions, contracted heels, are club-footed, have ringbone, have a broken axis, or are long toed-low heeled. Some are imbalanced, too, even sweeping off to either side. Others have dishes or bulges while some are too small. Undulating coronets tend to pop up, too, and many sculpted feet lack medial-lateral and dorsal-palmar balance as well. Misshapen or small frogs also crop up sometimes. Or some hooves are "mechanical sinkers" in which the hooves have particularly long hoof capsules which may have been a desire to make the hoof larger. Yet the size of the equine foot isn't measured by the length of the hoof capsule but by the breadth of the coronet. A scientifically arrived equation for evaluating hoof size can be found in my post here.

Please note with (B) that this alignment shouldn't be confused when the foot is positioned backwards and the joints have to flex to keep the hoof connected to the ground. These alignments only apply to a horse standing square.

Conformation is an important issue with horse people and so it is with equine artists. It encapsulates so much of what the public keys in on, what many consider to be a "good sculpture." Being so, it ensures that our pieces will be authentic in a way that most people recognize. Through conformation we can also help to depict horses in a way that advocates for their wellbeing and even promote those structures important to us like breed type. So there's just no way to artistically capture the animal without also having to consider it on some level.

Yet its power isn't necessary expressed by following conformation tenets doggedly, but understanding them well enough to weigh them in context to our piece. What's necessary? What's optional? What's harmful? What's neutral? With a deeper understanding then, we can create work closer to our vision while still ringing true in the show ring. We might also begin to appreciate each horse more as an individual perhaps, delighting in their quirks as "flavor" rather than as flaws.

Studying conformation also opens the door to a whole new horizon of understanding this graceful creature though all its myriad forms and functions. It's neat to learn about the differences between a racing Quarter Horse, a cutting Quarter Horse, a reining Quarter Horse, a WP Quarter Horse, a Hunter Quarter Horse, and a halter Quarter Horse! So many options! We can gain more appreciation for this critter, too, as we explore what his body is capable of doing with just a few tweaks here and there. It can also be helpful to realize that conformational variety within a breed can be a good thing by accommodating versatility and appealing to many tastes.

Put it all together and the subject of conformation infuses a whole new level of fascination and possibility into our work. It definitely ensures we'll never run out of new things to sculpt! So have fun exploring the wonderful world of conformation! It's fun, not hard to learn, and adds so much dimension to our creative adventures!

"Recognizing the need is the primary condition for design." — Charles Eames