[About this time back in 2015, I wrote the "Mapping Out Success" post. Since then though, I've learned some new tricks I'd like to share with you. However, it seems I can't go back to edit that original post so let's just have a do-over!]

Introduction

It's easy to understand how equine anatomy helps create convincing realistic sculpture. But aside from the technical know-how it provides, it also offers anatomical landmarks to use as guides. This is because these landmarks identify the dimensions, orientations, and placement of the bones and fleshy bits themselves, letting us better visualize and so translate anatomy into our clay. So an understanding of anatomy doesn't just provide the brass tacks for sculpting, it also gives us the means to put it all together. In this sense then, these landmarks can be likened to a kind of anatomical map, or “equine topography," that gifts us with some handy benefits for sculpture.

For starters, we get fixed points to measure proportion and gauge biomechanics regardless of the pose. We can then approach sculpting like a connect-the-dots, and because these landmarks universally apply, we can tackle anything we wish. Even more, fixed points promote structural symmetry, a welcomed benefit because—as just about any sculptor will tell you—symmetry is a tricky nut to crack! Going further, equine topography helps us decipher references and life study more accurately, making our process that much easier and clarifying our knowledge base. And because it's the blueprint for Equus, it's consistent across ages, genders, individuals, breeds, types, and species, letting us capture these variations more authentically. Put all that together and equine topography becomes a powerful tool that takes our work to the next level.

There are two layers to equine topography—the skeletal and fleshy. The subcutaneous, easily-palpated bone serves as the skeletal landmarks while muscle group configurations and cartilaginous formations form the fleshy landmarks. We shouldn’t rely on just one though since each informs the other.

In order to use these landmarks, however, we need a few tricks up our sleeve. First, good proportional calipers are essential; they're truly a sculptor’s best friend. For that, I recommend the Prospek® proportional calipers (Figure 1). Second, a lockable compass is very handy for quick measuring. Third, a protractor, preferably one made of clear plastic with a pivoting ruler (Figure 2) measures angles such as for the shoulder, hip, pasterns, and hooves. Fourth, develop a pretty good idea of how the skeleton is constructed and where the joints are located because we need to find all this in life study, our references, and our sculpture regardless of movement. Fifth, form a working idea of the muscle layers and major muscle groups to better interpret what’s happening under the skin. Sixth, a set of good illustrations or charts showing these landmarks, and bodyworking resources are great for this. And seventh, cultivating the habit of checking all these landmarks throughout the sculpting process, start to finish. It's easy for things to go awry when we're so deeply immersed in sculpting. Plus, the actual physicality of sculpting can smoosh fixed points off the mark, so our rule of thumb is: Check often, sculpt, and then check again.

Skeletal Landmarks

Learning the skeletal landmarks isn’t difficult. The best way is to gently palpate them on real horses, visualizing the whole skeleton as we go. For this, it's also a good idea to have an anatomy chart and some landmark illustrations on hand to quickly orient comparisons. But if up close and personal isn't possible, gaining access to a real equine skeleton or a well-done sculpture of an equine skeleton can be useful, too (such as found in Zahourek Systems EQUIKENTM)). I also highly recommend the anatomy classes taught by Lynn A. Fraley. Also catch the live streams by Morgen Kilbourn on her Facebook studio page. Nonetheless, anatomical illustrations are immensely helpful as well, specifically equine bodyworking sources which are often full of landmark charts and those that show the orientation of the muscles to the skeleton. And sometimes we can find helpful how-to videos on YouTube, too, such as this one. Some other resources and books are also super helpful in this department as well such as Horses Inside Out and Anatomy In Motion (and their materials), Equinology and Anatomy In Clay classes, and others. (Just a caveat though with anatomical features painted onto the skin: Horse skin is tacked down onto the underlying flesh rather loosely in many areas and so it's not always a totally accurate indicator of what those underlying areas are actually doing. However, this technique is great as a basic start for further investigation!)

Then it's time to hone our eye by practicing, working to recognize these landmarks to find the whole skeleton inside regardless of pose, breed, type, age, species, etc. It's also important to See the landmarks in any media or format so working to visualize the skeleton in a ceramic sculpture, a Zbrush sculpture, a felted sculpture, or in a photo, on a computer screen, or in video, for instance, is incredibly useful. And consider drawing on printed out images to further train our Eye because once we can see “into” horses, we can see “into” our sculpture. To that end, here are some basic skeletal landmarks to get started:

Fleshy Landmarks

Muscles, cartilages, and other fleshy components of the body attach to the skeleton in certain configurations, allowing many of their groupings to serve as landmarks for sculpting. So it’s important these fleshy features are oriented correctly on our sculpture since one askew feature can cause other things to shift out of place. Every little thing on our sculpture warrants our absolute attention (which is one of the reasons why this art form can be mentally exhausting at times by asking for a high degree of sustained focus). This is another reason why rechecking often is so critical: We want to catch our inevitable moments of distraction.

Fleshy Alignments

The magenta dots are the basic joints* and the blue dots are the most basic bony landmarks. The magenta line indicates the location of the cartilaginous joints of the ribs** (not the bottom of the ribs). The muscles groups are very simplified to clarify how the skeleton relates to them. It's also important to know how each joint articulates because they don't all move the same, but that's another blog post for another time. (*Each rib is also articulated with two adjoining thoracic vertebrae and with cartilaginous joints with the sternum, but I thought it would all be too confusing to show.) (**There's no cartilage connecting the ribs like that, but I thought a line just showing where the joints are located would be less confusing than a series of floating dots.)

Now this may sound like a rather daunting task, but it’s actually a fortunate correlation because once we can see the skeleton inside our sculpture, laying on the fleshy parts is that much easier. It works in reverse, too! In and of themselves, the muscle groups can help us tease out the skeleton since their origins, insertions, and arrangements are clues to the underlying bony counterparts.

Proportions

How the dimensions of the body parts relate to each other is a foundation of realistic sculpture. Well, truth be told, it could easily be argued that everything boils down to proportion alone. Think about it: Can't everything we do actually be expressed in terms of proportional relationships? It even helps to distinguish between the age groups, genders, species, types, and the breeds. It's so fundamental, in fact, that a single misstep can instantly compromise our illusion outright, or depict a technical, age, gender, type, breed, species, or conformation flaw. And there's no compensation for a proportional flaw either—once it's made, it can only be fixed. For instance, if we've made the head too big, there's no making the tail bigger to balance it out. Or if we've made one cannon bone longer than the other, there's no making the forearm shorter to make up the difference.

Yet measuring proportion can be a mystifying process that can lead to some problematic assumptions. For example, some may simply go by "eye" and hope for the best. Now this can work to some degree, but it's often better to rely on more objective means in a technical art form. On the other hand, some may search for a magic formula that will churn out the needed measurements as though nature could be expressed by a single, simple equation. Or some may come to the conclusion that certain breeds have a cookie-cutter set of dimensions that should apply to all individuals of that breed. Or going further, some even insist that their preferred proportional measurements should be applied across the board regardless of individual, breed, species, age, or gender variations. It all boils down to this: In the face of so much confusion, a very simple system that removes it is desired, and that's perfectly understandable. We just have to be careful we don't simplify things so much that we're actually removing critical information from our process.

Because the truth is that proportion is complicated and is best learned through practice, study, and experience. There's also no equation, no formula, or even One True System. However, it does require a goodly understanding of anatomy and that can be a rather daunting prospect. Complicating matters, proportion is highly variable, being more like a lottery of measurements than a formulaic equation, and that can be really overwhelming. Put all this together then and measuring proportion can prove itself to be quite intimidating.

But the other truth is this: Proportion really isn't so hard once we recognize the landmarks, making it more easily decipherable, learnable, customizable, and buildable. So if we do our homework and pay attention, we'll develop that bigger knowledge base for finessing judgement calls, nuances, and diversities. And we can develop our own system and take as many measurements as we wish to help us along, too. And that's a key point: The methods for gauging proportion are as individualistic as the artists themselves—what may work for one won’t for another. For instance, I’ve tried numerical measurements but I simply cannot make this method work for me though it works beautifully for others. So it’s a good idea to experiment with many different approaches to find one we don't "fight" because, absolutely, the last thing we want is to be at odds with our own methods!

Even so, it still holds true that effectively measuring proportion is best done with reliable tools like calipers. Creating realistic equine sculpture isn't like painting a landscape that can be fudged, but instead requires technicality and precision. And we have to be able to translate standing proportions to moving ones with relative ease. Moreover, having a measuring system that's quickly adaptable is handy to customize or make adjustments on the fly. The system should also be sensitive enough to account for the individuality of the subject along with the breed, type, gender, age, and species, and all their nuances. On the other hand, if we're sculpting an iconic archetype, the system should also be able to dampen individual components to favor an amalgam of individuals as a generic specimen. In other words, it should be able to average results. There's this, too: Certain features are vulnerable to problematic fads like the penchant for abnormally heavy muscling, really short heads, long, spindly cannons, small joints, tiny muzzles, or small feet that have been bred into some breeds. So a proportional system that can recognize that and compensate where we want is useful to have in our toolbox as well.

So for what it's worth, the method for measuring proportion presented here fits all this criteria, being one I've developed and used for years—perhaps you'll find it to your liking, too. It’s quick and easy, it accounts for individuality, it’s readily adaptable and customizable, it applies to any position, it can be averaged out with ease, it can quickly recognize fad-based changes, it's easily translated from resources, and it utilizes, even amplifies over time, our natural penchant for visual evaluation. But it does rely on a good understanding of equine topography, and the better our understanding, the more effective this system.

I've used a "baseline horse" here (above), an English Thoroughbred mare. This breed makes a great "basic horse" with its classic lines and timeless proportions. Just please note that certain proportions here reflect mare-ish tendencies such as the slightly longer back and bigger ears. Mares can also have finer necks and sometimes shallower jaws, or at least, less robust jowl musculature. Mare hooves should also be a good size to bear the weight of pregnancy well.

Now the pink dot on the shoulder is the point of shoulder (which is actually the cranial external tuberosity of the humerus) which establishes the length of the shoulder (which really is a bit of an arbitrary measurement since the actual end of the scapula is just above that tuberosity). However, please know that the little blue portion at the top of that red shoulder line denotes the space between the top of the scapula and the wither, i.e. that's not actually scapula right there. The yellow dot on the neck is the base of the neck, where the last cervical vertebra connects to the first thoracic vertebra, establishing the length of the neck. The orange dot on the hindquarter is the big knob on the femur right behind the joint to establish the length of the femur (or we can measure from the joint if we wish). The black dots on the legs represent the actual joints, first the one between the humerus and the radius, and the second between the tibia and the tarsus.

Now please caveat here: It's what measurements are taken, how they're taken, and where they're taken that's the system here, not the actual depicted lengths. That's to say each of these lengths is highly variable based on individual, age, gender, breed, type, or species tendencies so please don't interpret hers as dogma that applies to every equine. Instead, these specific lengths apply to this specific mare. What's more, the system here is basic so add more measurements as needed.

Now please caveat here: It's what measurements are taken, how they're taken, and where they're taken that's the system here, not the actual depicted lengths. That's to say each of these lengths is highly variable based on individual, age, gender, breed, type, or species tendencies so please don't interpret hers as dogma that applies to every equine. Instead, these specific lengths apply to this specific mare. What's more, the system here is basic so add more measurements as needed.

Also note that measurements are based mostly on the bones rather than the fleshy "outline." This is because flesh changes with conditioning, movement, individuality, breed, age, even gender, which means standard measurements based on them only apply when standing, right? Once movement begins, those fleshy measurements go out the window. This is why the measurements from the Ellenberger book (or those like them), for example, can get us into trouble rather quickly. However, bony dimensions don't change so if they're our fixed measurements, chances are good we'll be okay no matter the pose. Even so, we should know how the joints function—individually, regionally, and holistically—to understand how some things can appear to comparatively lengthen or shorten due to folding or bending, which can appear to happen in certain movements. (That being said though, if we're sculpting a direct portrait or directly from a photo, we'll need to take a lot more measurements than those depicted here, even those that account for those fleshy proportions.)

But how this system works is simple: Structural relationships are standardized into four measurements based on one standard measurement, the head (measured from the poll to the end of the muzzle). The three other measurements are 1/2 the head, 1/3 the head, and the femur length (which varies a lot, which is why it's a separate measurement). So this is where a lockable compass comes in handy—once that head measurement is taken, it’s locked, making it a simple task to apply it throughout the sculpting process. But, wait—it gets better! Take a piece of paper and draw out the head, 1/2 head, 1/3 head, and femur lengths, then with the proportional calipers we can now use those measurements to quickly apply them with ease. And we can arbitrarily make the head any length we want, automatically scaling the others in turn. So, in practice, I create a proportional reference chart for my sculpture based on my preferred reference photo. I print it out and then use that paper to keep those lengths so everything is in one place. Very handy!

Here, for example, is the primary proportional guide I'm using for Guaperas, my "yelling" Criollo stallion (I have one other to provide more options). You can see the four measurements I'm using in the black box, but the actual ones I'll be using are penciled in at the bottom. This way I can use my calipers to quickly apply them to my sculpture of him. Note how different his proportions are compared to the Thoroughbred mare? Proportion is a critical factor in breed type since a breed can have a very distinct set of proportional tendencies that define its look. By the way, I'm using other references for his head because I don't want to be sculpting this specific individual—I just need an idea of the basics for the breed.

And this is the proportional guide I'm using for Sage, the piece based off my feral mare medallion. Note how I've doubled up on the leg measurements between the one-half and femur measurements. It's okay to do that since a little bit more information never hurts. And again, notice how her measurements are very different from Guaperas who was different from that Thoroughbred mare? Try to come to things with an open mind since we may learn something if we're lucky! And, really, if I tried to pigeon-hole Sage into those TB mare measurements, she'd totally lose her distinctiveness and authenticity. But like with Guaperas, I'm going to tweak her head a bit so I can sculpt it more like my medallion.

Use this method over time and it actually starts to train the Eye to key in on proportional relationships and even errors rather quickly. A method that actually refines our Eye! Also note that we can take many more smaller incremental measurements against the head as we need such as for the eye, the cannons, the muzzle, etc. In other words, simply making things a fraction of the head measurement turns the process into a relatively easy and highly adaptable one.

Also note that I haven't provided measurements for the width of things from the front or back, as in the breadth of the brow, neck, chest, or hindquarter. These actually do better with eyeballing and specific reference, at least for me, since they're highly variable due to conditioning, nutrition, age, breed, or individual variation (as is the case with the brow). So use good specific references in these cases. For example, the width of the Atlas bone, the first cervical vertebra that attaches to the head, varies between individuals and breeds. (However, a neutral baseline to make needed adjustments is this: An Atlas breadth about as wide as the brow.) Or the brow is also variable with individual and breed characteristics with some breeds having a tendency towards narrow brows (and heads) whereas others having wide brows (and sometimes corresponding crowns). Foals also have their own unique tendencies in brow width. The chest also tends to vary a lot since the scapula, being attached only by flesh, also has muscles underneath it that can be bigger with conditioning, nutrition, or genetics, effectively widening the chest. This is one of the reasons why many chunky drafters and stocky Quarter Horses have such wide chests: There's a lot of muscle bulk not only above but also below their scapulae. But it's also one of the reasons why Big Lick TWHs have such wide chests: Those weighted packages muscle everything up. Conversely, it's why malnourished horses are so narrow since their subscapular musculature is shrunken. This is similar to why foals can be so narrow because they haven't yet developed the muscle bulk to help "pooch out" their scapulae.

The head itself also has some measurements we can take, in my case I like to mostly go off a 1/3 head measurement. Just keep in mind that the head is highly variable so feel free to tweak or add measurements as needed—it's all customizable. Again, however, remember that what measurements are taken, how they're taken, and where they're taken is the system here. The actual proportions themselves belong to this specific mare. (Also note that ear length can be a function of breed type such as native British ponies who usually have proportionally small ears. Stallions also tend to have smaller ears.)

Symmetry

Symmetry applies to the bilateral halves of the animal, and so each paired feature should be as closely matched as possible. For example, eyes should be matched and level, leg bones should be of equal paired dimensions, muscle development should be consistent, the pelvic "box" should be perfect, zygomatic arches should match, ears should mirror each other, etc. But we also have to consider that, like us, horses have slight asymmetries, too, which is perfectly fine in a sculpture given it lies within the bounds of what would be acceptable in life. But beyond this, there’s rarely a more effective way to obliterate our sculpture than looking head-on at flounder-like eyes or having asymmetrical legs with one cannon quite shorter than the other, for instance.

But while bilateral symmetry is important, it’s not the easiest thing to achieve. Indeed, it's often the bane of a sculptor's existence! I took a WizardCon sculpting workshop and the instructor and I got to chatting about the challenges with symmetry, and he admitted he loved sculpting zombies because that was never a concern! And let’s face it, too—every artist has their “good side” and “bad side” of working (perhaps because of handedness) so it’s understandable that many dread having to match the other side once the preferred one is done. But there's some good news: Once we grasp equine topography, we're one step closer to making this painstaking process easier because rechecking the landmarks tends to naturally guide us to symmetry. Really, if we get the landmarks right on both sides, we definitely have a better shot at matching them. But be sure to check symmetry from all angles. For instance, we may get the zygomatics symmetrical from side views, but look at them from above and we see one is significantly protruding farther away from the skull than the other. Symmetry is a tricky thing.

We can also run into symmetry problems with our ability to flip images in our heads—some people can do it and some can't. Either way, if we want to check ourselves, a handy trick is to snap a photo on our phone of both sides, get them into a photo editing program and, with one slightly transparent, overlay them to see where they line up or where they diverge. Do this enough times and we can actually train our Eye to refine this ability pretty closely by itself.

Now here's a handy tool I got years ago from Mountain View Studios, Inc. (below), but I don't think they make them anymore. It came in two sizes: Large and small (I got both). Maybe you can make one for yourself since it's just a rigid metal rod with 90˚ resin cube-shaped cross bars. The top bar is fixed, but the bottom bar slides, tight enough to grab. But what you do is simple: Place it down the center of the sculpture's face in the front and use the crossbars to evaluate how level the features are to each other on either side. Easy and handy!

Visual Tricks

Nonetheless, equine topography also incorporates artistic visualization tricks that make deciphering it a little bit easier. For example:

- The knee and the hock, from the front, can be a bit trapezoidal.

- The hindquarter, from the side, can be a bit diamond-shaped.

- The nostril is like a reversed 6 on the left side and a 6 on the right.

- The muscles on the forearm form a "W," as do that of the gaskin a bit, too.

- The barrel is a bit canoe-shaped with a narrow keel between the forelegs and a broad, flat-bottomed stern.

- The cheek muscling on the head forms a "W."

- The "salt cellar" of the zygomatics form a "U."

- A basic head alignment follows a line below the bulb of the ear to the "button" of the zygomatics to the bottom of the nostril (and sometimes the bottom of the eye though it can be above that line with many equines). The line of the mouth can somewhat parallel this at times as can the line of the teardrop bone a little bit, too. However, keep in mind that this linear alignment diverges with individuals, breeds, and species. For instance, horses with some convex or some concave heads will diverge from this straight line, sometimes markedly so. Therefore, this alignment is only a springboard baseline for needed adjustments—we have to start somewhere!

- The "button" of the zygomatics aligns with the back of the jaw (since it sits right over the jaw joint).

- The points of hip, the points of buttock, the femoral joints, and the tips of the Ilium (tuber sacrale) form a perfect symmetrical "box," because that box, the pelvic girdle, doesn't articulate internally.

- The wing of the Atlas (first cervical vertebra) is about a hand's width away from the back of the jaw.

- The simplified musculature of the neck (well conditioned) often forms a basic "M" with a hook that veers up to the wing of the Atlas bone.

Now all of these are just basic ideas, and there are plenty more, but the point is this: Try to distill things down into easy-to-grasp shapes and alignments to use as baselines for comparisons and adjustments. When we deconstruct and simplify things, we can start to demystify equine topography, making it easier to decipher our references and sculptures. Now then pair this with proportion and symmetry, and we're well on our way to a successful sculpture! (Then add in placement and planes and we're essentially set, so stay tuned for the next blog post on The Three Ps for more discussion on them.)

As just a bit of curiosity, it's interesting to notice how the equine is built on a kind of mirror image (below). Just like how each bone is moved by sets of antagonistic muscles, so the body plan is built on a "reflection" of itself. This may seem like a rather obvious observation, but it's curious how many art works, especially animated works, get this wrong. Perhaps the Pushmi-Pullyu really does exist after all!

As just a bit of curiosity, it's interesting to notice how the equine is built on a kind of mirror image (below). Just like how each bone is moved by sets of antagonistic muscles, so the body plan is built on a "reflection" of itself. This may seem like a rather obvious observation, but it's curious how many art works, especially animated works, get this wrong. Perhaps the Pushmi-Pullyu really does exist after all!

Some Proportions That May Surprise Us

So once we familiarize ourselves with this system, or whatever system we choose, it's time to start exploring and investigating the similarities and the options. They're there! Gather a bunch of photos then and just start noting the tendencies and differences within any given grouping. And be sure to study different groupings! Indeed, "10 year old Arabian stallion" can go into age, gender, and species groups, not just breed. And don't forget about old photos! If we can make comparisons against older archetypes of a breed, for instance, we gain some perspective. Make all this a regular exercise and we'll start to amass a mental library of the possibilities. Now here's the thing—we don't have to remember all the different lengths. That's not the point of the exercise. The point is this: To beat into our noggins that variability is the rule, that tendencies are what's typical, that what's acceptable is a bubble, a spectrum. So trying to cram all this diversity into a cookie-cutter opinion of "The Only Right Measurement" will likely cause problems. That's to say this exercise should quickly chip away at our own dogma about what "should be" and instead present what can be. And that's a great thing, yes? It now means we have so much more possibility to play with in our clay, and our expectations have likewise been loosened up a bit to appreciate them more. Being able to See and appreciate more equine awesomeness? Sign me up! Indeed, many breeds, for example, are characterized by variability of type so to insist that only one of them is the "real" version unfairly dismisses perfectly good representatives. As artists we have the opportunity to celebrate all of horsedom, and all horses are worthy our admiration and respect. Any which way, we make a habit out of exercise, and we'll not only train our Eye, but also gain a better footing to make more balanced judgement calls while still picking out those esoteric nuances for flair.

Comparing proportional measurements with these landmarks may also gift us with some surprising revelations. Truly, the divergence of what the mind thinks it sees and what’s actually there is interesting! The stylized depiction of equines is a rather common thing in art, too, and so many have become conditioned to favor certain stylized proportions that aren't necessarily consistent to reality. For example, unnaturally short backs, exceedingly short heads, or abnormally large eyes (perhaps as a function of neonatal characteristics) can be relatively common stylistic distortions. Yet nature created the horse’s back, for example, to be a certain length to accommodate the necessary viscera to breathe, digest grasses, or to gestate foals. The more the back is shortened, the more these things are compromised. This isn’t to say that a long back is a good idea, but that there's a normal spectrum optimal for the animal’s biology, but we only learn that through a lot of proportional comparison. However, we often find that this normal spectrum can be considered “too long” by those otherwise conditioned. Or if we have a particularly long and sloping shoulder, that can also create the illusion of a "longer back" for those not familiar with proportional measurements. Likewise, a long hip can make the torso appear "too long" as well. Then add those two together and...well...it can throw off the unfamiliar eye. Yet it's only through a good grasp of equine topography that we can weed through all this to nitty gritty what's really going on.

Conversely, we may find that some sculptures have necks that are unnaturally long. But the more the neck is lengthened, the more the cervical bones are lengthened which stresses the ligaments and tendons that hold the chain of cervical vertebrae together along with the nerves that govern movement. This is why those horses bred with really super long necks have a tendency for subluxations, muscle issues, uncoordinated motion, and nerve damage. Yet only in art can we find this extreme made even more so, and one wonders if a firmer grasp of topography may have mediated this. It's understandable though as the neck is one of the hardest features to sculpt due to its biomechanics that seem to make it "shorten" or "lengthen" in motion. Truly, if any feature more needed a grounding in topography, it would be the neck!

Then when we begin to measure in smaller increments, we'll find that the horse's eye isn't as big as some sculptures depict. Gosh—some have orbits so big, one wonders how the cranium could accommodate! We'll also find that ears are variable in size (and shape) as are nostrils and muzzles. Even the width between the jaw bars varies, too. Some proportions also touch on conformation concerns like cannons and joints that are a bit too small, or tailbones that are too skinny (or anatomically too long or too short).

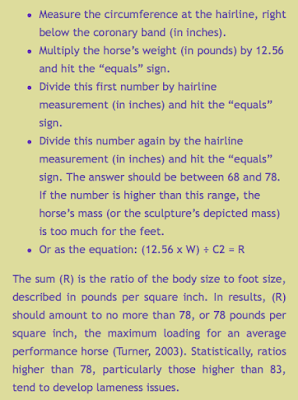

Now interestingly, science has established a more objective formula for determining the preferred size of the hoof—an actual equation:

Scaled down, we can apply this ratio by estimating how many "inches" our sculpted coronets are in circumference and then estimating the "living weight" of our sculpture then plugging those numbers into the equation. Pretty soon then we'll develop a mental library of hoof sizes that fit inside this spectrum for a short cut. (We also come to learn that hoof size isn't gauged by the length of the hoof wall, but by the circumference of the coronet band.)

Conclusion

Absolutely, understanding equine topography not only makes our process easier and more accurate, it also frees us to design sculptures from our own vision rather than being enslaved to specific photos all the time. Just as much, too, we can objectively study how real flesh morphs and the living body behaves, something which no static anatomical chart can illustrate. This means we're now able to use our Voice in full confidence to express all the wonder of the equine world we discover or imagine. In essence, we gain a better hold on the technical aspects of this art form so we can better express our artistry.

Even more though, understanding equine topography keeps us curious by propping those proverbial doors open to the possibilities out there. When we start adopting rigid expectations, we shut out a lot of the equine world from our clay and that's a shame. There's so much to explore and love out there, and armed with a practical topographical understanding, we have a great toolbox to express it.

Yet perhaps most importantly, equine topography reveals that all equines are individuals, blessed with infinite variations on the blueprint, which can only serve to inspire creativity and deepen our appreciation for this remarkable creature. It's so easy to be lured into habitual objectification in the pursuit of "perfection" or what is "correct." So quickly we fall too much in love with our opinions, but equine topography lets us peer into a world fuller and richer than our expectations. Letting the equine guide us, with his road map in hand, won't only steer us to our fuller potential, but reveal just how much potential wonderfulness there is out there to enjoy! Truly, equine topography represents the keys and the doors to explore all of equidom, so snatch them up, bust 'em open, and happy trails!

"Geographers never get lost. They just do accidental field work."

~Nicholas Chrisman

(Go here to download my 2020 Anatomical Reference Listing. New additions are in red, and in particular, scroll towards the end of the listing for "Device Apps," a new category with some great resources for you!)

(Go here to download my 2020 Anatomical Reference Listing. New additions are in red, and in particular, scroll towards the end of the listing for "Device Apps," a new category with some great resources for you!)