Our journey through life is a meandering path, isn't it? Sure—we like to think of it as a diligent march forward, goal in sight with steadfast gaze and detailed map firmly in hand. But the truth is that despite our resolve, it's all just rambling. And though we may have some inkling of what we're doing, none of us really have any idea of where we're going. How could we? Life is unpredictable, and we're all just wingin' it.

Honestly, I look back over my life and wonder what would my 10–year–old self think of my now. How I am now. And I think that's a good thing. We may still hold onto memories, but we become many different people throughout our lives. We're wanderers in our own unfolding adventure.

And that keeps our options open, doesn't it? This blissful, blind freedom to choose our paths, even when we're unaware we're making choices, characterizes the collage of our lives. And if we "big picture" it all, these unique twists in our evolving odyssey not only contribute to who we are, they eventually test who we are, too. And in 2013, I had the opportunity to engage such a test.

And that keeps our options open, doesn't it? This blissful, blind freedom to choose our paths, even when we're unaware we're making choices, characterizes the collage of our lives. And if we "big picture" it all, these unique twists in our evolving odyssey not only contribute to who we are, they eventually test who we are, too. And in 2013, I had the opportunity to engage such a test.

And in that "me" category was my creativity—my art work—the very core of my being. I'm not exaggerating when I say that my art is me and I am my art. To not create my art is to essentially cease being me. Like not breathing anymore. And what's so insidious about clinical depression is how easily it chiseled away at this very core of who I was, something I thought impervious. So there I existed, stripped bare of all that I was, stuck in a reality utterly devoid of identity, purpose, and emotion. I was nothing. This is the power of clinical depression. To continue existing for one more moment—at that point—is the insane decision. It's madness—but such a blessed madness it is.

So when I eventually emerged into the light with recovery, I was left deeply shaken, and full of self–doubt about my ability to create art—even about my will to create art. For the first time in my life, I was hesitant, afraid, and distrusting of myself and my abilities, and saw a horizon in which my art didn't blaze the trail. Did clinical depression destroy who I had been so completely that art simply wasn't in the cards anymore? Could it be that my survival came at the expense of the old Sarah, leaving in her place this doppleganger in the mirror? Another Creatures song, I Was Me, kept ringing in my head.

I realized I had just emerged from an alien landscape and found myself in an even stranger one. I stumbled along, trying to make sense of this uncomfortable new self I'd become, disliking her, wishing she'd go away. I missed myself—mourned for my old self. I tried to coax her back, but I feared she was gone forever. I was so very lost. Afraid and lost.

I realized I had just emerged from an alien landscape and found myself in an even stranger one. I stumbled along, trying to make sense of this uncomfortable new self I'd become, disliking her, wishing she'd go away. I missed myself—mourned for my old self. I tried to coax her back, but I feared she was gone forever. I was so very lost. Afraid and lost.

Then out of the blue came an email from Stephanie Majecko of Breyer—would I be interested in sculpting a piece for their Premier line? Specifically an appealing pony broodmare? A Connemara–ish pony broodmare who could also plausibly be other breeds, too? Whether one believes in coincidence or not, the critical serendipity of this invitation is hard to escape. Indeed, this inquiry came at such a pivotal moment in my life, I consider it a personal Black Swan Event. It'll forever define that moment when I had to choose…choose to fight for who I was or remain this unwelcome thing I didn't recognize.

I realized in that moment that I had to earn my art back. I had to fight on an internal battlefield to reclaim it and reignite its flame.

Strange, isn't it? Every once and a while a golden opportunity opens its arms to you. But only every once in a blue moon, such an opportunity invites you precisely when you need it most, as though the Universe conspired to give you a leg up onto that proverbial horse. And this piece for Breyer, Dancing Heart, was exactly one of those blue moon moments for me.

Cuz, seriously…talk about a childhood dream come true! I remember being that little girl with a new, out–of–the–box Breyer in my hot little hands. (And oh!—that heady aroma!) I remember my bedroom shelves lined with my treasured Breyer horses as a girl, carefully arranged and lovingly oogled. I even remember dreaming of sculpting for Breyer when I "grew up" (whatever that means!), about bringing to life the same magic in plastic for others. And here it was—BAM. To be able to (hopefully) give that gift to someone else is a joy beyond description. It's full circle.

Plus, the idea of my work being mass–produced is more than a welcome approach to me—I eagerly seek it. Art is for sharing, for connecting and communicating, so my motto in this sense is The More The Merrier! Because previously I'd focused on my own limited resins, customs, and originals, but now I could tap into the collections of OF (Original Finish) enthusiasts as well. Best of all worlds! How could I say, "No"?

But at first I was full of trepidation. How could this Golden Ticket come to me right at the moment when my taste for candy was so dubious? That lingering self–doubt just poisoned my creative well still so badly. Then I realized this could be framed as a test. If I could pull this off in the full vision the project needed to be realized, then it was possible to regain my former life. This sculpture could be the proverbial battleground. So I jumped in full throttle and cried, "Banzai!"

So to start the project, Stephanie—who was a wonderful partner in all this—presented the specific needs of the project, and we worked together to come to a final decision after chatting about a concept that would be both feasible and appealing. And that's the tricky bit in all this: when it comes to mass production, getting "feasible" and "appealing" to intersect can be the pesky part. Going into this, I already knew it wouldn't be easy for me from that standpoint alone. Ordinarily, I'm not used to such design limitations, all the "don'ts." I'm accustomed to flexible silicone molds and small editions that allowed for fussy bits or the coddling of tricky areas. I'm inured to creating pieces dictated only by how I wished them to be, without much of a care, without all the "you can't do thats." Just ask my moldmakers—their grey hairs tell the story!

Ooooooh, but not so with this sculpture! Oh no…this piece was the exact opposite set of criteria, defined by nearly every "don't" you can imagine. No undercuts, no tendrils, no thin bits, no pockets or dips, no depressed cavities such as the bottoms of the feet, the tailbone/dock area, or under the jaw. Basically anything that could hang up on the mold or require careful fiddling was clean off the table. Even the head couldn't be turned too much. On top of that, a base was out of the question, yet Heart needed firm points of solid contact since no one wants a tippy model! But wait, there's more…she had to fit inside that famous Breyer box, and that dictated more limitations for the head and neck, legs, and mane and tail, as you can imagine.

But these aren't complaints, mind you—these "don'ts" exist for very good reason! Heart wasn't one of my artisan editions, but destined for mass production, and that required a shift in design precepts. It's just the nature of the beast. Indeed, how a Breyer gets created is quite a feat of production engineering. Plastic is melted into a liquid and then shot into a two–part, rigid metal mold. It's then de–molded, glued together, with any gaps filled with molten plastic, then seam–cleaned and smoothed for painting. The amount of work just to get a casting paint–ready alone is mind boggling—and this has to happen exactly the same, without a hitch, over and over and over.

And it's all those "don'ts" that ensure this sequence won't get interrupted or compromised so that each casting will be as faithful as possible to the original sculpture. So for the first time, I had to essentially "sculpt flat." That is to say, each side had to pull cleanly, straight out from the side without hooking onto the mold in any way. And the cleaner it would pull, the more faithful the casting would be.

All of that in mind, Heart also had to stand out in the Breyer catalog, she had to have that eye–appeal and hold her own over the long years she'd be in production. And despite all the "don'ts," too, she had to really grab you. Not so easy! So with all this whirling around in my head, I whipped up five preliminary sketches exploring different ideas, and sent them to Stephanie. Because I was new at this, looking back, there were some wild ideas in those sketches—now I know better! Ha ha! So in the end, Breyer chose Sketch #2b, one which would fit the bill perfectly—it was feasible and appealing, a combination not so easy to concoct.

The next step was amassing a smorgasbord of references and distilling them down into one archetypal individual based on the qualities I believed would serve the project best. Luckily I was given free rein to independently research and convey Dancing Heart as I saw fit, and thankfully so since my best work is produced when I'm left to my own devices. Now what struck me most perhaps about the Connemara was the degree of variation within the breed. Some looked like tiny Andalusians, some like small Thoroughbreds, some like wee Hunters, some like Half–Arabs, with a whole menagerie in between. I read through several sources of breed requirements and found that much was left open for that variation to manifest—which is great!

After some pondering then, I decided to create a big–bodied, big–boned mare, a heavier kind of Connemara, since that would be a unique niche for the Breyer line, and open up some fun possibilities for future runs of "pony." So I took inspiration (and measurements) from a herd of champion Connemara mares as well as ideas from here, here, here, here, here, and here and conjured up an archetype that would serve as the template for Heart. So while she was Connemara–ish, she could pass as other types of ponies, too. Breyer's only real stipulation was that Dancing Heart be pretty—be that beautiful, little pony broodmare we all love in our hearts, and happily we were already of the same mind about that! Woot!

So it all starts off with an individual soul, a personality or character, and what it wants to convey to the world once complete. And this little soul wanted to be that special blend of lovely and puckish, beautiful but loaded with presence and moxy, that fun kind of pony–quirkiness that's so darned endearing. If that wasn't enough, she had to have the substance and style of "pony power," that quality that makes them so stout and sturdy. I researched like crazy, and took so many measurements and cross–references, I was dreaming them in my sleep!

On top of all this, Dancing Heart had to look like a broodmare, with their unique proportions and that special "soft" look of of an experienced Mother—that sweet, wistful look of a Mom who knows her child will grow up and plot their own course in life. I hope I achieved that. I think I did. I studied a lot of broodmares for this, and I had my previous research from sculpting Elsie, too, so I was well–equipped. I also drew much from my own Mom—she being the best Mom ever! (Hi, Mom!) She has unfailingly supported my pursuit of art, making sacrifices, listening to my worries, offering advice, and always offering encouragement and unconditional love. In many ways, Dancing Heart is an hommage to her—a kind of, "I love you, Mom—thanks!"

From my perspective then, coming to these conclusions was easy since it seemed we were all of the same mind on most aspects already. Stephanie trusted me, and that in turn, inspired my trust in the project. It was wonderful! And Kitty Cantrell, who has sculpted several pieces for Breyer already, offered some most welcome advice, since I'd never sculpted for plastic–injection before. For instance, she suggested I sculpt in the details a bit harsher than normal, since the plastic softens ridges and depressions just a bit. That one tidbit really helped to realize all of Heart's bells n' whistles better for the final product. Thank you, Kitty!

All said and done though, Dancing Heart was designed for the horse–crazy kid we're all still at heart. She's that pony who dances in our dreams, embodying all that's wondrous, free, and limitless in horse form—and that's a universal message.

It's also a tall order! I'm pretty much self–taught, lacking formal art education. It's been discipline, diligence, and pro–active research—and the willingness to follow it wherever it led— that has formed the basis of my development. I gravitate towards what's novel, fresh, and sideways, but a above all, I go where this animal leads me. And Dancing Heart had a very important quest for me…and it was now time to start sculpting…

Each posture presents its own curiosities to explore and narratives to tell—even a standing horse is moving! Yet for a moving posture, you have to think from the spine down to the hooves whereas with a standing horse you need to think from the hooves up to the spine. So getting Dancing Heart to balance properly on a three–point stance would be tricky when keeping the final plastic version in mind. No one wants a model that'll tip over!

A 3–point stance is definitely the easiest way to achieve all this, but it does present its own challenges. A lean too far in any direction means instability just as quickly as anything else, and a base wasn't an option. I wanted her to be as solid as a rock, to be as close to an even tripod stance as possible, but without sacrificing one iota of that lovely equine motion we find so appealing.

Now I suppose compared to other approaches, my process appears chaotic and unschooled, but to me it's quite straightforward. And while I have a very clear image in my head, down to each detail, I allow the piece to evolve on its own because no matter how clear a concept may be, no on ever knows it all at the onset. So I let the piece guide and teach me in ways only that piece could. In this sense then, my process is instinctive and visceral while also focused on learning—but not only about technique and equines, but about myself, too. In many ways, it's a meditation. A sanctuary. I'm not just focused on the journey though—I have to finish what I start. There was a looming deadline! So I'm very much a "destination" kinda girl, too. I don't believe the journey is the sole repository of insight. Enlightenment can be most profound in the moment we can say "done" with confidence.

As for the nitty–gritty, I always start with the withers and shoulders, then work my way out, basing all measurements on the pre–determined head length. I find this allows for a more free–flowing approach, and from this viewpoint, I suppose my process can be best described as organic.

I had a difficult time getting the head just right for a large–ish pony mare. And symmetry is important, too!

Having worked with this head–measurement method for so long, my brain is fast to key–in on disproportionate sections quickly. I'm a very fast sculptor. Now granted, that said, I invariably get the back length too short in the initial stages, so I'm always having to lengthen it as one of the final steps! We all have our quirks.

Strange, isn't it? Every once and a while a golden opportunity opens its arms to you. But only every once in a blue moon, such an opportunity invites you precisely when you need it most, as though the Universe conspired to give you a leg up onto that proverbial horse. And this piece for Breyer, Dancing Heart, was exactly one of those blue moon moments for me.

Cuz, seriously…talk about a childhood dream come true! I remember being that little girl with a new, out–of–the–box Breyer in my hot little hands. (And oh!—that heady aroma!) I remember my bedroom shelves lined with my treasured Breyer horses as a girl, carefully arranged and lovingly oogled. I even remember dreaming of sculpting for Breyer when I "grew up" (whatever that means!), about bringing to life the same magic in plastic for others. And here it was—BAM. To be able to (hopefully) give that gift to someone else is a joy beyond description. It's full circle.

Plus, the idea of my work being mass–produced is more than a welcome approach to me—I eagerly seek it. Art is for sharing, for connecting and communicating, so my motto in this sense is The More The Merrier! Because previously I'd focused on my own limited resins, customs, and originals, but now I could tap into the collections of OF (Original Finish) enthusiasts as well. Best of all worlds! How could I say, "No"?

But at first I was full of trepidation. How could this Golden Ticket come to me right at the moment when my taste for candy was so dubious? That lingering self–doubt just poisoned my creative well still so badly. Then I realized this could be framed as a test. If I could pull this off in the full vision the project needed to be realized, then it was possible to regain my former life. This sculpture could be the proverbial battleground. So I jumped in full throttle and cried, "Banzai!"

So to start the project, Stephanie—who was a wonderful partner in all this—presented the specific needs of the project, and we worked together to come to a final decision after chatting about a concept that would be both feasible and appealing. And that's the tricky bit in all this: when it comes to mass production, getting "feasible" and "appealing" to intersect can be the pesky part. Going into this, I already knew it wouldn't be easy for me from that standpoint alone. Ordinarily, I'm not used to such design limitations, all the "don'ts." I'm accustomed to flexible silicone molds and small editions that allowed for fussy bits or the coddling of tricky areas. I'm inured to creating pieces dictated only by how I wished them to be, without much of a care, without all the "you can't do thats." Just ask my moldmakers—their grey hairs tell the story!

Ooooooh, but not so with this sculpture! Oh no…this piece was the exact opposite set of criteria, defined by nearly every "don't" you can imagine. No undercuts, no tendrils, no thin bits, no pockets or dips, no depressed cavities such as the bottoms of the feet, the tailbone/dock area, or under the jaw. Basically anything that could hang up on the mold or require careful fiddling was clean off the table. Even the head couldn't be turned too much. On top of that, a base was out of the question, yet Heart needed firm points of solid contact since no one wants a tippy model! But wait, there's more…she had to fit inside that famous Breyer box, and that dictated more limitations for the head and neck, legs, and mane and tail, as you can imagine.

But these aren't complaints, mind you—these "don'ts" exist for very good reason! Heart wasn't one of my artisan editions, but destined for mass production, and that required a shift in design precepts. It's just the nature of the beast. Indeed, how a Breyer gets created is quite a feat of production engineering. Plastic is melted into a liquid and then shot into a two–part, rigid metal mold. It's then de–molded, glued together, with any gaps filled with molten plastic, then seam–cleaned and smoothed for painting. The amount of work just to get a casting paint–ready alone is mind boggling—and this has to happen exactly the same, without a hitch, over and over and over.

And it's all those "don'ts" that ensure this sequence won't get interrupted or compromised so that each casting will be as faithful as possible to the original sculpture. So for the first time, I had to essentially "sculpt flat." That is to say, each side had to pull cleanly, straight out from the side without hooking onto the mold in any way. And the cleaner it would pull, the more faithful the casting would be.

All of that in mind, Heart also had to stand out in the Breyer catalog, she had to have that eye–appeal and hold her own over the long years she'd be in production. And despite all the "don'ts," too, she had to really grab you. Not so easy! So with all this whirling around in my head, I whipped up five preliminary sketches exploring different ideas, and sent them to Stephanie. Because I was new at this, looking back, there were some wild ideas in those sketches—now I know better! Ha ha! So in the end, Breyer chose Sketch #2b, one which would fit the bill perfectly—it was feasible and appealing, a combination not so easy to concoct.

This was sketch #2, and Breyer chose option "b," the head down–version. As you can tell, I'm a sculptor, not a flatwork artist. To me, a sketch is simply a basic idea, not a full drawing. I wanna get sculpting!

The next step was amassing a smorgasbord of references and distilling them down into one archetypal individual based on the qualities I believed would serve the project best. Luckily I was given free rein to independently research and convey Dancing Heart as I saw fit, and thankfully so since my best work is produced when I'm left to my own devices. Now what struck me most perhaps about the Connemara was the degree of variation within the breed. Some looked like tiny Andalusians, some like small Thoroughbreds, some like wee Hunters, some like Half–Arabs, with a whole menagerie in between. I read through several sources of breed requirements and found that much was left open for that variation to manifest—which is great!

After some pondering then, I decided to create a big–bodied, big–boned mare, a heavier kind of Connemara, since that would be a unique niche for the Breyer line, and open up some fun possibilities for future runs of "pony." So I took inspiration (and measurements) from a herd of champion Connemara mares as well as ideas from here, here, here, here, here, and here and conjured up an archetype that would serve as the template for Heart. So while she was Connemara–ish, she could pass as other types of ponies, too. Breyer's only real stipulation was that Dancing Heart be pretty—be that beautiful, little pony broodmare we all love in our hearts, and happily we were already of the same mind about that! Woot!

So it all starts off with an individual soul, a personality or character, and what it wants to convey to the world once complete. And this little soul wanted to be that special blend of lovely and puckish, beautiful but loaded with presence and moxy, that fun kind of pony–quirkiness that's so darned endearing. If that wasn't enough, she had to have the substance and style of "pony power," that quality that makes them so stout and sturdy. I researched like crazy, and took so many measurements and cross–references, I was dreaming them in my sleep!

All said and done though, Dancing Heart was designed for the horse–crazy kid we're all still at heart. She's that pony who dances in our dreams, embodying all that's wondrous, free, and limitless in horse form—and that's a universal message.

It's also a tall order! I'm pretty much self–taught, lacking formal art education. It's been discipline, diligence, and pro–active research—and the willingness to follow it wherever it led— that has formed the basis of my development. I gravitate towards what's novel, fresh, and sideways, but a above all, I go where this animal leads me. And Dancing Heart had a very important quest for me…and it was now time to start sculpting…

I like to use aluminum wire or wire coat hangers for my armatures! You can see that I've articulated the joints as close to an actual skeleton as possible, keeping symmetry and proportion in mind.

I use foil to built up the initial bulk of the piece.

A 3–point stance is definitely the easiest way to achieve all this, but it does present its own challenges. A lean too far in any direction means instability just as quickly as anything else, and a base wasn't an option. I wanted her to be as solid as a rock, to be as close to an even tripod stance as possible, but without sacrificing one iota of that lovely equine motion we find so appealing.

Now I suppose compared to other approaches, my process appears chaotic and unschooled, but to me it's quite straightforward. And while I have a very clear image in my head, down to each detail, I allow the piece to evolve on its own because no matter how clear a concept may be, no on ever knows it all at the onset. So I let the piece guide and teach me in ways only that piece could. In this sense then, my process is instinctive and visceral while also focused on learning—but not only about technique and equines, but about myself, too. In many ways, it's a meditation. A sanctuary. I'm not just focused on the journey though—I have to finish what I start. There was a looming deadline! So I'm very much a "destination" kinda girl, too. I don't believe the journey is the sole repository of insight. Enlightenment can be most profound in the moment we can say "done" with confidence.

I use a cheaper epoxy putty to add further bulk. You can see here that I've cut and readjusted her limbs a bit—you always have to be open to necessary adjustments! She's rather gruesomely suspended by two wire hooks suspended from my studio ceiling while I make these adjustments.

As for the nitty–gritty, I always start with the withers and shoulders, then work my way out, basing all measurements on the pre–determined head length. I find this allows for a more free–flowing approach, and from this viewpoint, I suppose my process can be best described as organic.

Now I start using my preferred epoxy putty for the real sculpting!

I usually sculpt the eyes in last. She looks waaaay funky here, doesn't she?

Here you can see how my eyes start as blobs which get refined throughout the epoxy cure time.

You can see I've had to cut her apart at her barrel and lengthen her just a snidge. I've also started work on her mane and tail. The tail was the easy part, but the mane was tricky. It has to compliment the piece and the face while also following the rules of passive physics, yet still pull from the mold cleanly each time! That means no extreme undercuts or too many artistic liberties. The plastic–injection molds are rigid, not pliable like with resin casting, and production, which has to be speedy and reliable, can't be compromised by anything that would catch on the mold parts.

Checking myself to make sure I stay true to the project! You can see the adjustments I had to make to ensure she stands, but still maintain the spirit of the original design.

I like to use a wire mesh for mane and tail armatures. It provides lots of flexibility and versatility, so this is how they get started. You can find this wire mesh at most craft stores.

Here's her final head and mane. I wanted to color in her eyeball with a pencil to see if I caught the expression I wanted in crisp detail.

In the end, with a breath of relief, I looked at her with great satisfaction. I hit my every criterion, plus those requested by Breyer. She was exactly the pony broodmare we had all envisioned! And I hoped and hoped she would inspire that childhood magic we all felt when we held that blessed Breyer box tightly in our eager little hands on some Christmas morning or Birthday afternoon. I paused and marveled at how this animal, the horse, and Breyer had influenced so much of my life, personally and professionally. They'd always been there, and now I could give back, so to speak. I could contribute to that wonderful alchemy. Heart could make that magic for someone else, and what a lovely feeling that was. I'll hold it close to my heart for the rest of my life.

No small matter, though. Creating Dancing Heart had been a tremendous challenge because despite all my own priorities for her, I had to deliver a piece according to the strict parameters of the mass–production process and the project requirements all the same. It was a curious task to see how far I could push my more freestyle approach up against those boundaries without bursting beyond them. Fortunately, the Breyer team I worked with were absolutely splendid. The kind of room Breyer granted me to bring her alive fed back on itself, and really propelled the whole sculpting process forwards—I'm very grateful! Cuz—hey—they even let me give her a "pooky" lip, whisker bumps, and eyelashes! That's unprecedented!

No small matter, though. Creating Dancing Heart had been a tremendous challenge because despite all my own priorities for her, I had to deliver a piece according to the strict parameters of the mass–production process and the project requirements all the same. It was a curious task to see how far I could push my more freestyle approach up against those boundaries without bursting beyond them. Fortunately, the Breyer team I worked with were absolutely splendid. The kind of room Breyer granted me to bring her alive fed back on itself, and really propelled the whole sculpting process forwards—I'm very grateful! Cuz—hey—they even let me give her a "pooky" lip, whisker bumps, and eyelashes! That's unprecedented!

Done! Now to smooth with sandpaper and detail in the veins, moles, chestnuts and little fiddly bits. Then with a coat of primer, she's off to the caster to have resin production masters made! PHEW.

Twisty fun!

In the end, through it all, I was also elated to find that I had won the psychological battle for my art—for my old self. A bit bloodied perhaps, but unbowed. Apparently that part of my old self was still in here, eager to come out but buried under the wreckage of depression's storm. It needed something truly monumental to be coaxed out, a universal cry to muster up its bravery—a real motivation to get back into the fray again. It needed something worth dying for, I suppose, and Heart was definitely that! She was worth one last epic effort, yet rather than being my last swan song, she ended up being the calvary galloping into my salvation! It was Dancing Heart who came charging into the rumble as a trusty steed to faithfully carry me through! How unexpected—how wonderful! And even more surprising, I found that I wasn't just my old self again—I was better than I was before. Indeedy, subroutines had been at work the whole time, processing sculptural information below my consciousness to make Heart and my post–Heart work better. The whole experience also made me a better person. What a surprise! Heart had enriched my own.

A box o' Hearts, fresh from my caster! Thank you Barry Moore of BearCastLLC for your superb craftsmanship! I couldn't have done this without you!

So from internally crippled to Dancing Heart—it's a literal metaphor. To those currently suffering from clinical depression, I'm here to tell you that you can survive that mental mindfield. Find something good—anything—that motivates you and grab onto it fervently. It's your guide back to the light. Dancing Heart saved me and my art. How curious that what first got me going down the path of realistic equine sculpture—my Breyer horses—would be the very same thing that would swoop down to my rescue all these years later. Again, full circle.

Cleaned, packed, and off to their famous destination, Breyer Animal Creations, with the help of one of my trusted Post Office buddies, Steph, otherwise known as "Mayhem" to her cohorts! Steph, you're famous!

I now measure my career as pre–Dancing Heart and post–Dancing Heart, this particular equine soul being that instrumental in my life. I cannot convey with words how reaffirming and wonderful it is that Breyer afforded me the unique gift of sharing this strange, personal journey with you. It's a beautiful thing. I sculpted her just for you, and I hope she brings you as much joy as she gave me as I brought her to life. I'm now back in the saddle, so to speak, so thank you, Dancing Heart! Thank you, Breyer! And I thank you, you. With Dancing Heart, you travel this marvelous journey shared between all of us, hand in hand, hoof to hoof. And so my final wish for you is…

May your heart always dance!

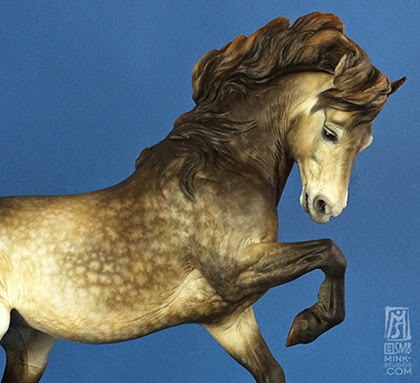

Colorway #1: Sooty dappled buckskin, painted according to specification.

I am perplext, and often stricken mute.

Wondering which attained the higher bliss,

The wing'd insect, or the chrysalis

It thrust aside with unreluctant foot.

~ Thomas Bailey Aldrich